Beyond the Catch-22 of the “deserving poor”

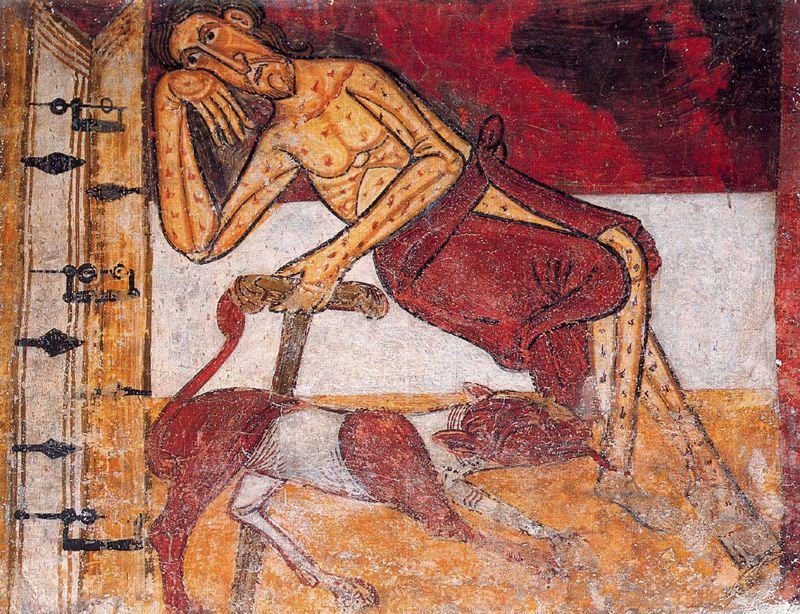

11th century fresco; initially located in Saint Climent de Taüll, Spain; now at the Museu Nacional d'Art de Catalunya.

Wonderings…

I wonder if you’ve ever experienced “schadenfreude”—if you’ve ever been glad at someone else’s suffering, because they really had it coming?

I wonder if you ever got something you didn’t deserve?

Reflection on those Wonderings + Texts for Year C, Proper 21

Amos 6:1a,4-7; Psalm 146; Luke 16:19-31

Let us speak, and listen, held in the presence of our loving, liberating, and life-giving God. Amen.

I got a call around 8 o'clock on Friday night from our artists in residence, Pau and Felize of Bad Student. They were working in their studio—this room here, and somebody was at the top of the stairs here, and he wasn’t well, and he was screaming that he needed help. The double doors were locked, so this person couldn’t get into the sanctuary, but Pau and Felize were scared nonetheless.

So I put my collar on and rushed over, to find a man outside these doors, pressed up against the window, addressing Jesus on the cross up there. He is deep in prayer; he is crying, he is angry, he is drunk.

He tells me that he has come because he is desperate to stop drinking. He’s looking for help; he tells me he has been to 3 other churches tonight, but they all kicked him out. They wouldn’t help him because he was drunk.

He’s asking for help because getting drunk every night is ruining his life; but people won’t help him because he’s drunk.

I did my best to help him, gave him a number of a 24 hour AA hotline, walked him home so he wouldn’t buy beer on the way…and it didn’t go very well: the point of sharing this story isn’t to toot my own horn, or to rag on these other churches he tried.

I’m telling this story because I think the catch-22 this man found himself in points us to the crux of this parable that Jesus tells, about starving, suffering Lazarus and the rich man who steps over him every morning, coming out his front door on his way to the office.

I don’t think this parable is about what happens when we die; I think this parable is definitely about money, and how the gross inequity of wealth in Jesus’ society and in our own deforms all our souls. And I think it’s about something maybe even more fundamental than money.

I’m going to take an imaginative leap and guess that the rich man doesn’t feel compelled to help the poor man at his gate because the very fact that Lazarus needs help proves that he’s not the kind of person that deserves help. I think this is a legitimate presumption for two reasons.

Human beings have not evolved at all since the time of Jesus. We’re exactly the same kind of creatures we see depicted in the Bible. And many of the rich people in our society are convinced that they became rich entirely through their own individual effort, and people who are poor or suffering are in that condition because they just haven’t tried. They haven’t taken responsibility for themselves, so they don’t deserve help from anyone else.

I also think there’s a clue in the context of this parable: Jesus is addressing this parable to a particular audience. Of course he’s talking to the community that has gathered around him; people from across the social hierarchy who are experiencing healing and liberation in his presence, and in community with one another. But he’s also talking, obliquely, to the peanut gallery. The people who are ridiculing him, heckling him from the cheap seats. Luke calls these people Pharisees.

And it cannot be said enough, given the way that Pharisees have been caricatured through Christian history, often through an anti-Jewish or antisemitic lens: these Pharisees don’t have it out for Jesus because they are Jews and he’s a Christian. Jesus wasn’t a Christian; he was a child of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob just like the Pharisees. These Pharisees aren’t malevolent monsters; they are deeply pious people who are understandably threatened by Jesus’ teaching and scandalized by the movement that has gathered around him, because it pushes on a core belief they have about how the world works, and how God works.

And that belief that good things happen to good people, to people who make good choices. #blessed. And they also believe that, if somebody is suffering, then on some level, it must be their fault. They must deserve it. So their relationship to the suffering of others has at least a hint of judgment, or even contempt.

Again, human nature has not changed in any fundamental way since the time of Jesus. So when you hear the word “Pharisee,” I invite you to imagine someone in your life who does not struggle with something you struggle with, and who has lots of ideas about why your struggle is ultimately your fault.

You’re struggling to afford rent, or can’t dream of buying a home? Someone says You must be frittering your money away. I saved diligently, and I don’t see why you can’t do the same.

You’ve come to the Southern border of these United States fleeing ecological devastation, or to protect your spouse from death threats from a local gang, or because you can’t bear it anymore, to have your kids drink a half gallon of water before bed each night so hunger pangs won’t wake them up. Someone says you’re not doing it right. There are rules, and we don’t want the kind people who won’t follow the rules in our country. (And, by the way, we reserve the right to change the rules.)

You’re suffering from complex symptoms of long COVID, and your boss says you don’t deserve accommodations because you’re just not trying hard enough. You wait for months to see a specialist, but then your insurance claim is denied; and the person who finally picks up the phone after you’ve been on hold for 90 minutes says you didn’t go about it in the right way—if you read the fine print of your benefits, you’ll see you actually needed pre-approval. C’mon, it’s not that hard.

The community that has gathered around Jesus—they know from personal experience that the system is rigged; they know that the law doesn’t add up to justice, and is often deployed as a tool of injustice. And they might well hear this story as a gratifying fantasy, a reversal of fortunes. A promise that they, in their suffering, are held in the bosom of their ancestor, father Abraham.

But what is Jesus saying to the Pharisees, these people who can’t see the contingency of this world, who refuse to acknowledge structural factors, who believe their success is a reflection of their individual righteousness, and that the suffering of others is a reflection of their sin? Is Jesus saying You’re going to burn in hell?

I don’t think so. If Jesus were saying that, it would have been the punchline of the story. Lazarus and the rich man both died; Lazarus was carried away by the angels; the rich man went down to the fire. The end. But the reversal of fortunes piece, that’s actually pretty close to the beginning; it’s part of the setup. I think Jesus is giving the Pharisees a chance to empathize with suffering people, to imagine themselves, for once, on the punishing end of an ‘unbridgeable chasm.” The kind of chasm that exists between rich and poor, then and now. The kind of chasm that exists between people who could help someone with an alcohol problem, but won’t help a drunk.

I also think Jesus is puncturing the piety of these Pharisees, and puncturing their conception of who God is, as an underwriter of their self-righteousness. What is the actual punchline of this story? No, rich man, we’re not going to send you back to warn your brothers to change their ways, ‘If they do not listen to Moses and the prophets, neither will they be convinced even if someone rises from the dead.’”

Jesus is making a point about the tradition that he and the Pharisees share as children of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. That tradition insists that care for the poor and vulnerable is at the heart of anything God would call justice. As we read in our psalm, “the Most High cares for the stranger; God sustains the orphan and widow, but frustrates the way of the wicked.”

Jesus is saying, hey, remember that God despises any piety that isn’t reflected in your relationships, and especially your relationships with the most vulnerable. Holiness isn’t reducible to rule-following. You can’t ignore the poor and call yourself pious because just you say your prayers. Our spiritual health and wholeness is bound up with our neighbors’.

And I think Jesus is saying one more thing to these Pharisees—which might be important for us to hear as well. Because I bet everyone in this room has felt the satisfactions of self-righteousness, has held another in contempt. On Friday night, when I encountered that man here at the church, I confess that my first thought was Oh God I don’t want to waste any time on some hopeless drunk.

If we listen to Moses and the prophets, we hear of a God who is restless for true justice, actual equity among God’s children; and we hear of a God who never gives up on anyone. Who never abandons those who suffer, those caught in the throes of illness or addiction; and we hear of a God who never stops seeking after those who have gotten lost in the fog of status-seeking and self-righteousness, who have lost the thread of what integrity looks like.

And so, friends, God is saying to the part of each of us that is ashamed and the part of us who is the contemptuous judge—I will never stop seeking after you, to bring you back to yourself, back to wholeness, back to the love and care that is yours because you are mine.

Amen.