The Big, Beautiful Bill and the Good Samaritan

In our three year cycle of scripture readings, the Gospel lesson appointed for this Sunday is the parable of the Good Samaritan. This year I’m reading it anew in light of the terrifying turn our political life has taken, and the partisan narratives that harden our hearts against our neighbors.

Just then a lawyer stood up to test Jesus. "Teacher," he said, "what must I do to inherit eternal life?" He said to him, "What is written in the law? What do you read there?" He answered, "You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your strength, and with all your mind; and your neighbor as yourself." And he said to him, "You have given the right answer; do this, and you will live."

But wanting to justify himself, he asked Jesus, "And who is my neighbor?"

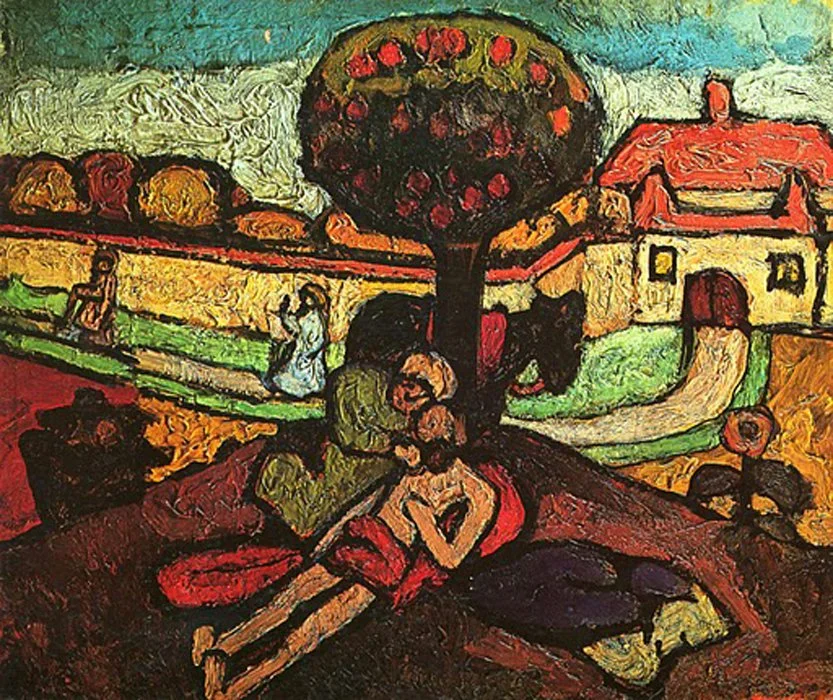

Jesus replied, "A man was going down from Jerusalem to Jericho, and fell into the hands of robbers, who stripped him, beat him, and went away, leaving him half dead. Now by chance a priest was going down that road; and when he saw him, he passed by on the other side. So likewise a Levite, when he came to the place and saw him, passed by on the other side. But a Samaritan while traveling came near him; and when he saw him, he was moved with pity. He went to him and bandaged his wounds, having poured oil and wine on them. Then he put him on his own animal, brought him to an inn, and took care of him. The next day he took out two denarii, gave them to the innkeeper, and said, `Take care of him; and when I come back, I will repay you whatever more you spend.'

“Which of these three, do you think, was a neighbor to the man who fell into the hands of the robbers?" [The lawyer] said, "The one who showed him mercy." Jesus said to him, "Go and do likewise." (Luke 10:25-37)

The “Good Samaritan” is famous enough to have laws named after him; he even made it into the finale of Seinfeld. And the story about him is fairly well known; it’s about the care that every human being deserves, and the everyday cruelty we choose when we harden our hearts to the struggle and suffering of others.

On First Reading

One week after the passage of President Trump’s “Big, Beautiful Bill,” this story’s themes of compassion and care are as compelling and challenging as ever. This bill declares that it is more important to give huge tax breaks to the richest Americans than it is for the most vulnerable among us to have the support we all need to survive and the care we all need to thrive. Budgets are moral documents: they declare our priorities and enact our values.

This bill is a work of bureaucratic cruelty, and it is written in our name. Cuts to SNAP benefits mean that more children will go to bed hungry. Cuts to Medicaid mean that millions of people will be kicked off their health insurance, and that people with disabilities will lose services they depend on to survive. Staffing cuts at the Social Security Administration, the VA, and other federal agencies means that hurting people will suffer under an increased “time tax.” They’ll have to wait in longer lines and endure more paperwork delays just to be approved to...wait in another line for the actual care they need.

Any faithful reader of the Good Samaritan story would recognize its call for us to reevaluate our priorities and to ask what values we are enacting. The priest and the Levite who pass by the wounded man are often treated as villains. But I see myself in them: they’re not bad people—they didn’t beat him up! It’s just that their ritual duties in the Temple require them to be ritually clean. And the rules say they can’t come into contact with blood or any other bodily fluids.

The priest and the Levite aren’t unconcerned with this person’s suffering; it’s just that they haven’t budgeted time and energy to help. They have other priorities: this human suffering is an unwelcome intrusion into the day they’d planned for themselves. I know that I’ve turned away from moral responsibilities countless times, for the same reason.

What makes the Samaritan “good” is that he is willing to put aside from his other business and put the care of the vulnerable at the top of his to-do list. The story challenges us to make the Samaritan’s priorities our own: to respond with mercy and compassion when we encounter the suffering of others—even people very much unlike us.

The “Big, Beautiful Bill” does the opposite. It elevates the financial interests of the ultra-wealthy by taking away support and care from suffering people who are currently receiving it. And it does it with the pernicious lie that some people—some “others” don’t deserve such care.

On Second Reading

Jesus taught in parables, and parables are more than morality tales. They don’t hammer on one simplistic “take-home” message: parables use paradox and surprise to expose unexamined prejudices and provoke new perspectives. So, if you’ll stick with me for a minute, I’d like to explore another layer in this story of the Good Samaritan: a layer that richens its challenge for us in these times.

By “in these times” I mean that we are immersed in battles for political power in which the other side is routinely dehumanized. By “in these times” I mean that those political battles are enmeshed in struggles over status. Our social life is steeped in competing attempts to “one up” each other, to vent our resentments and flaunt our contempt. Such contempt is corrosive to the social fabric, and it corrupts the political process through which we make decisions about our shared future.

This parable of the Good Samaritan is also about that. Note Jesus drops this parable into a particular situation, talking to a particular person. The text identifies him only as “a lawyer”—somebody who specializes in the fine points of the Law of Moses—but we can get a pretty compelling picture of this person from his short exchange with Jesus.

Just then a lawyer stood up to test Jesus. "Teacher," he said, "what must I do to inherit eternal life?" He said to him, "What is written in the law? What do you read there?" He answered, "You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your strength, and with all your mind; and your neighbor as yourself." And he said to him, "You have given the right answer; do this, and you will live."

But wanting to justify himself, he asked Jesus, "And who is my neighbor?"

First, the text says that he wants to “test” Jesus, by asking what is necessary to inherit eternal life. Jesus turns the tables on him, asking him in turn what he sees written in the law and the prophets. Jesus challenges the lawyer to put some skin in the game, and, as it turns out, his answer resonates with the primary thrust of Jesus’ teaching in Luke’s Gospel: "You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your strength, and with all your mind; and your neighbor as yourself."

Jesus and this lawyer are testing each other—feeling each other out—in a way we can immediately recognize. They are each trying to figure out if they need to have their defenses up, or if they can be real with each other. It seems like this lawyer isn’t trying to cut Jesus down or trap him; it seems like he’s testing to see if Jesus is the real deal—if Jesus is living out the convictions that the lawyer shares. And Jesus in turn is trying to figure out if the lawyer is genuinely exploring what it means to live with integrity in faithfulness to the God of Israel, or if he’s asking these questions in order to score points in a debate.

What makes the lawyer a compelling character in this story is that he’s doing both. He’s earnestly and humbly seeking to learn from Jesus AND he’s trying to prove how smart he is. The lawyer doesn’t let the conversation end with him and Jesus in surprising agreement about the focus of a faithful life. He wants to push it further; he wants “to justify himself.”

In other words, this lawyer is playing a status game. He can’t help it: it’s what he’s been trained to do. He tries to get one up on Jesus. “A-ha…but who is my neighbor?” (I confess that my mental image of this lawyer looks a lot like the philosophy bros that I sometimes hung out with in college…and that maybe, sometimes, I was…)

What does Jesus do in response to the lawyer’s desire to justify himself? He presents this parable of the Good Samaritan. So here I want to think about the parable of the Good Samaritan as not only a reply to the content of the question “who is my neighbor?” but as Jesus’ response to the lawyer’s instinctive attempt to draw Jesus into a status game.

And to understand what the parable is doing on this level, we have to understand something that would have been obvious to the people around Jesus and is perhaps less obvious to us now. Everybody hates Samaritans. For the people around Jesus—from Galilee, and later, from Judea—Samaritans are down on the lowest rungs of the status hierarchy, and everybody loves to punch down on them. They are the butt of jokes. They are viewed with contempt.

The word “Samaritan” is said with the same tone of voice we hear today with language like “lib,” “cuck,” “deplorable,” “Trumper,” “ACAB”...

The list could go on for a while. But perhaps that’s enough to stir up the gut-level feelings those words invoke: righteousness, confident superiority, contempt.

Based on the lawyer’s response to his earlier question about what is written in the law and the prophets, Jesus knows that this guy is not going to be impressed by the priest and the Levite. Jesus knows that he’s going to feel compassion for this wounded man, and Jesus knows he’s going to identify with the person who helps him. So the parable is, on this level, a setup for this lawyer to feel connected to—even inspired by—somebody he would otherwise hold in contempt.

Unpacking this parable provokes the lawyer into an uncomfortable identification, a scandalous sympathy. His familiar status hierarchy has him at the top and Samaritans close to the bottom, but in the way Jesus tells it, that hierarchy begins to dissolve.

In Sum

The parable of the Good Samaritan challenges us to show mercy and care to those who are suffering—to make that our priority.

And, in the way it unfolds, this parable does something to the lawyer, listening to Jesus. It does something to us. It draws us out of the status games we play almost instinctively; it softens our hearts, so we can glimpse that the person we’ve held in contempt is just another person trying their best—and they might actually have something to teach us. Like the Samaritan, they might even inspire us to live out our own values more faithfully.

To bring it back to the challenge of our own times: As people who strive to follow the way of love that Jesus showed us, we’re called to fight against policies that prioritize the interests of the wealthy over the suffering of the poor. When our elected leaders make decisions, they do it in our name: we have to fight against cruelty in all its forms, and to fight for more extensive and effective forms of mercy.

But the second reading of this story reminds us of the dangers of defining ourselves over or against our opponents, or against an “Other.” When our sense of goodness or worthiness depends on scoring points in a status game, our sense of self-worth requires that somebody else be worth less, that somebody else be demeaned.

This is a subtle and radical call of the Gospel: to put aside the status we might gain at the expense of another, and to be drawn instead into the compassion and solidarity we discover when we focus on our shared vulnerability, our shared identity as children of God, our shared capacity for goodness and grace.